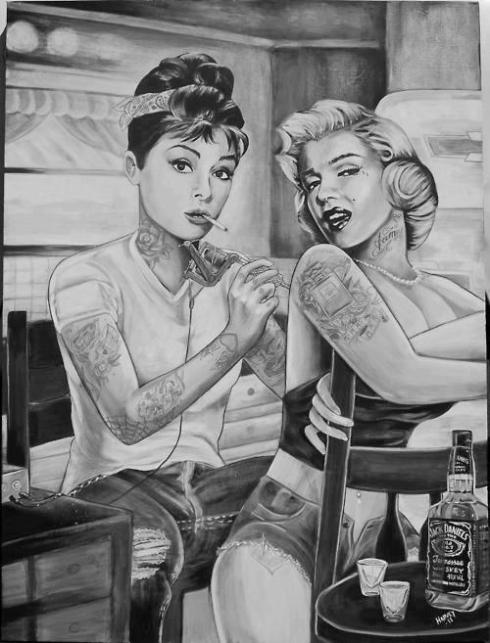

“Tattoos are in limbo – neither fully damned nor fully lauded.” (Roberts, 2012)

Argument

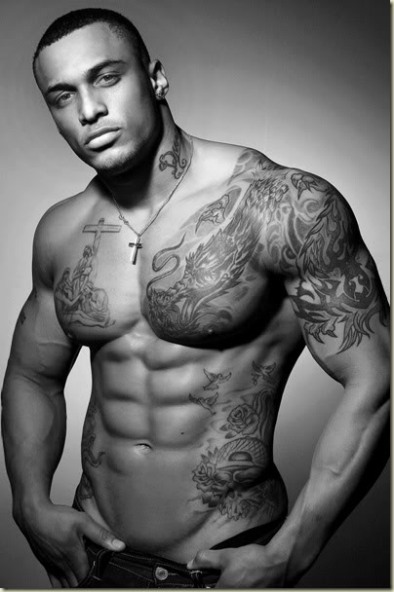

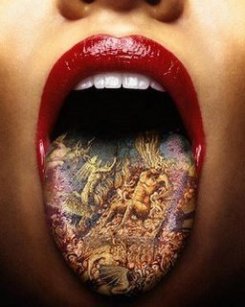

In his article, Secret Ink: Tattoo’s Place in Contemporary American Culture Roberts puts forth the argument that the tattoo and concurrently the tattooed in society currently find themselves in a unique position, between the older stereotypical and negative view of the tattoo as a symbol of deviants, and it’s new consideration as a socially acceptable self expressive force, even vogue statement of fashion, that today embellishes so much media as well as the carefully considered hidden ribs and backs of many of today’s middle class youths.

Methodology

In order to explore and ultimately prove his theory Roberts partook in a social experiment whereby acting as an “observer-as-participant” he took on the role of receptionist within a tattoo shop. With this role he was able to observe and record first hand, through a mixture of informal conversations, involvement with shop activities and tuning in to the conversations between clients and artists, the interactions between those within and those experiencing for the first time the culture of tattooing.

“First, I wanted to know why the client did or did not bring somebody with him or her. Second, I asked what the client was getting tattooed and sought to understand any significance attached to the design. Third, I inquired about the reason for the particular size and location of the tattoo.” (Roberts, 2012, p156 – 157)

Using the above specific questions Roberts was able to determine,

- The motivations behind the majority of clients choice to get a tattoo

- The possible affiliations or reasons for the choice of tattoo

- The clients reaction to possible stigmatization after the fact

Supporting evidence

Roberts found that the general motive behind getting tattoos largely contradicted the older social scientific notions of gang affiliation and, or criminal associations and was in fact a rather a lighter hearted “moment of deviance” for those bridging the gap between young and old, while a completely none deviant and perhaps even more light hearted purely self expressive act for those clients describable as today’s youths. He conveyed this dynamic perfectly through his desciption of the interaction between middle aged client “Betty” and younger company namely daughter “Maggie” and grandson “Joe.”

“Betty thought of getting a tattoo as an act of deviance and later told me that she would never have gotten the tattoo on her own or if she had to pay for it herself. She was tattooed with four other women, all of whom considered their tattoos to be their “walk on the wild side.” Although her mom and dad both considered tattoos deviant, Maggie, who was in her upper thirties, liked lager tattoos. As Betty and I were speaking, Maggie interrupted us:

[Maggie] Hey, how much would it cost. Just like that. The whole thing.(she was pointing at a flash piece of a chalice titled with wine splashing out from the top and a cross floating above it. There was banner around it which read last call for acohol.)…

[Betty](scoots to the edge of the couch and leans forward in order to see what her daughter is talking about.) oh you wouldn’t get that!?

[Maggie] sure I would.

[Betty] That big!?!?”

[Maggie] Yeah, on my back( points to the small of her back)

[Betty] No, that’s too much. That’s crazy.

This interaction between Betty and Maggie Provides a good example of the intergenerational cultural conflict that often surrounds tattoos. Not only did Maggie bring her son (who is a minor) to be tattooed, she was also interested in getting a tattoo that is approximately six inches by six inches. Even thought it would be in a hidden location, her mother still thought the tattoo’s size made it “too much.” In Betty’s eyes, it was on thing to get a small tattoo in a moment of weakness, but it was quite another to plan a large tattoo.” (Roberts, 2012, p159-160)

However despite the evidential shift in societal acceptance and belief systems surrounding the tattoo the older negative connotations were proved by Roberts still at large as the new age “tattooees” longed to contain their self expressions in places easily hidden if needs be, for potential disapprovers. The extent to which tattooees where willing to go to keep their statements optionally heard if you like even exceeded recommendations of excess pain proving a strong awareness that the negative connotations associated with tattoos were still live and well in some of today’s social circles, be them old or white collar.

This obvious awareness in the younger more accepting generation of the still smoking negativity of older societal beliefs is also echoed in the fact that Roberts found that two thirds brought someone with them not as originally stated by one client for moral support but rather due to an instilled distrust and discomfort entering the potentially “dangerous” habitat of the tattooed people!

“Among the 48 tattooees, 32 had at least one person accompany them… There were also 39 tattoo consultations during this period, 13 of whom came alone. It is interesting to notice that the ratio of individuals coming alone (one-third) and individuals coming with company (two thirds) was exactly the same for both people getting tattooed and people merely being consulted… this calls into question clients’ stated reasons for bringing moral support.” (Roberts, 2012, p157)

Furthermore Roberts continued,

“Although many clients, like Naomi, claim that it was merely a fear of pain that caused them to bring friends and / or family, the data suggests that this is an insincere claim meant to save face. If it were really a fear of pain that led the clients to bring moral support, then one would expect to find a clear distinction between the number of individuals who came in for tattoos with support and the number who came in for tattoo consultations with support. After all, if one is not getting a tattoo on a given day, there is little need to be concerned with physical pain…it is not likely that the clients were, in fact, afraid of pain. On the contrary, it was a fear of and lack of comfort with tattoo culture, as discussed by Eugene, which drove clients to bring support into the shop.” (Roberts, 2012, p158)

Alternative Hypotheses

When considering other critical theorists and their points of view Roberts exclaimed that,

“While the ‘Tattoo Renaissance’ (Sanders, ‘Marks’ 401) has led to a dramatic shift in the attitudes and arguments put forth by academics concerning tattoos, by no means are the old attitudes disappearing from the literature.”

Atkinson is a clear example of this as he states,

“The symbiotic relationship between tattooing and illegal behaviour (or otherwise unconventional lifestyles) still dominates in sociological research. Sociologists prefer to study the subversive subculture uses of tattooing. (Atkinson via Roberts, 2012, p153)

However there are certain critics adapting with the times as they admit that,

“[the tattoo] has undergone dramatic redefinition and has shifted from a form of deviance to an acceptable form of expression.” (Irwin via Roberts, 2012, p154)

There is a clear and definite split in theory here as some sociologist continue to argue the dominance of all negative associations with tattooing, while others attempt to manifest that a complete and utter shift in societal norms has occurred and tattoos are now socially completely acceptable.

In past studies Post and Steward argued that “the physical act of getting a tattoo would cause future deviance.” (Post and Steward via Roberts, 2012, p154) Roberts explains that Ferguson-Rayport, Griffith and Straus; Lander and Kohn all proclaimed a link between tattoos and criminals or the mentally ill in the past while their theories have been recently updated and expanded further by other researchers such as Brooks et al, Carroll and Anderson, Stirn, Hinz and Brahler, Wohlrob et al who “seek to convince readers of a link between tattoos and both mental health problems and (sexual) deviance.” (Roberts, 2012, p154)

While Rosenblatt claims “a vast expansion of tattoos among mainstream Americans since the late 1980s and early 1990s” (Rosenblatt via Roberts, 2012, p153) this in itself suggesting a positive change in societal acceptance in order to cause the increase.

Others such as Deschesnes, Fines and Demers as well as Koust agree that tattoos have become so widespread that they are now considerable as mainstream. (Deschesnes; Fines and Demers; Koust via Roberts, 2012, p155)

All in all it seems the critical masses either fall on one or other side of a very tall fence.

Conclusion

In contrast to the above decisive war denoting either complete new age positivity or consistent negativity in relation to the tattoo Roberts confirms for us a middle ground is much more likely to be the case in society today. His experiment conveyed neither a public utterly accepting of the tattoo culture nor a people stagnant in their negative perceptions from long ago but rather a transcient time of shifting views. A rare and exciting “in between” period where social norms are absolutely evolving in the young and yet the remainders of a lifetime of prejudice against the very same topic still exists in the older generations of communities. In this light some such as Bell attempt to diversify the argument even further using very valid points to suggest a difference between “the tattooed people” and those who get a tattoo or two

but if as Roberts states,

“On the one side, researchers portray tattoos negatively by focusing on deviance and mental disorders. On the other, scholars view tattoos as positively contributing to identity formation and fashion” (Roberts, 2012, p153)

Perhaps the point is not to get bogged down splitting hairs over who wins, the anti’s or the pro’s, but rather to embrace and enrich ourselves with the exciting and informed knowledge that theories and perceptions are becoming formed and undone under our very noses. That at this moment self destruction co-exists with self expression, remembrance of love and loss is immortalized alongside boasting’s of murder and other criminal activities. That an all encompassing pocket of human culture has somehow miraculously managed to bring together people from all backgrounds, classes, races and points of view to one momentary, fleeting yet united place of admiration for art, and how apt be it that this art, this moment, this experience, is one as unique, as it is, permanent.